So last entry, we discussed the 12 notes of the Western Harmony System, and gave every single one of them a name. Now, we're going to start organizing them in ways that are musically useful.

How many of you remember this woman?

Remember "Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti Do"?

Yes. Tonight, we're going to talk about the mother of all scales: THE MAJOR SCALE.

There are several scales at our disposal, and believe me, we're going to eventually cover all of them, but we have to start here, because this is the one scale from which all other scales are derived.

When I said it was the "mother of all scales," I wasn't kidding.

Then again, maybe you could make a case for the Chromatic Scale being the mother, but I don't. Just assume that the Chromatic Scale gave all of the others up for adoption, and since the Major Scale is the one who stepped in and did the job, she is the one we're honoring today.

(What the hell am I talking about.)

Ahem. Moving on...

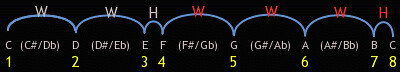

Here is a C Chromatic Scale:

Now... we come up with a Major Scale using an important formula known as TWO AND A HALF / THREE AND A HALF. Remember the WHOLE STEP and the HALF STEP from last time? We're going to organize them in this order:

WWH / WWWH

Two and a half on the left. Three and a half on the right.

Start with "C" and move a whole step (2 notes) to the right. We end up with a "D", right? Next, move another whole step to the right. The result is "E." That's two whole steps! Now we need to finish the "Two and a half" part of the equation with a half step. From "E", this ends up being an "F."

C - D - E - F.

Follow me so far?

We still have "WWWH" to deal with.

Starting with "F", we move a whole step to "G", a whole step to "A", a whole step to "B", and finally a half step to "C." THREE AND A HALF.

This gives us all 8 notes of a C MAJOR SCALE.

Let's isolate them from the rest for a few minutes:

It's probably all-too-apparent at this point why I chose the key of "C" for this exercise; no sharps or flats to deal with on this one.

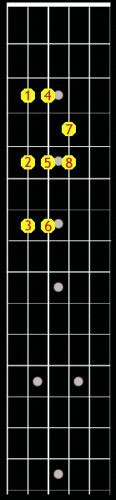

Now that you know the notes that make up a C Major Scale, here is where to find them on the neck.

First, let's look at the scale as if we were playing it on one single string. Notice the way that the WWH / WWWH relationship plays out on the fretboard of a guitar. We find our "C" starting on the 3rd fret of the "A" string.

"D" is on the 5th.

"E" on the 7th.

"F" on the 8th.

"G" on the 10th.

"A" is on the 12th fret, or the "snake eyes" as we like to call that area of the guitar neck.

"B" is on the 14th, and then "C" falls on fret #15, which corresponds to fret #3.

But nobody plays a scale all on one string, because that'd be a hassle. So here are two other ways that you can play the C Major Scale instead. The one on the left is commonly known as the "condensed" version, because all of the notes are compacted into a small area. The one on the right is called the "extended" version because you're going to have to stretch those fingers just a little more to play it. This doesn't mean it's any less useful.

EXTENDED:

EXTENDED:

Practice playing those two versions of the scale; memorize the shapes!

What we've done tonight is we've established an extremely critical framework for understanding all other scales. And that's not all. The implications of this are even more far-reaching than what it might seem at the moment.

So congratulate yourself on a job well done, and when we return next time, we'll begin talking about the "atomic particle" of music: the INTERVAL.